EDITING

def: The organisation of sequences to construct meaning.

Editing describes the relationship between shots and the process

by which they are combined. It is essential to the creation of

narrative space and to the establishment of narrative time. The

relationship between shots may be

graphic,

rhythmic,

spatial and/or

temporal.

Filmmakers and editors may work with various goals in mind.

Traditionally, commercial cinema prefers the continuity system, or the

creation of a logical, continuous narrative which allows the viewer to

suspend disbelief easily and comfortably. Alternatively, filmmakers may

use editing to solicit our intellectual participation or to call

attention to their work in a reflexive manner.

GRAPHIC RELATIONSHIPS

Graphic Match

(Grant Reed)

Graphic matches, or

match cuts, are

useful in relating two otherwise disconnected scenes, or in helping to

establish a relationship between two scenes. By ending one shot with a

frame containing the same compositional elements (shape, color, size,

etc.) as the beginning frame of the next shot, a connection is drawn

between the two shots with a smooth transition.

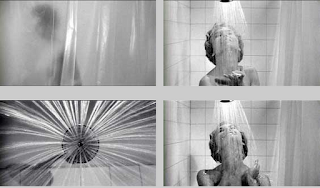

The first clip below, from Hitchcock’s

Psycho, takes place

just after a woman is brutally stabbed to death while in the shower. As

her blood washes away down the drain with the water, the camera slowly

zooms in on just the drain itself. A graphic match cut is then utilized,

as the center of the drain becomes the iris of the victim’s lifeless

left eye.

The next clip, from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, is

generally considered to be one of the most famous match cuts in all of

film. As a primitive primate discovers the destructive powers of his

newfound technology, the femur of a deceased animal, he tosses it high

up into the air. Thousands of years pass in a single moment as a

close-up of the bone cuts to a long shot of a satellite orbiting the

earth, thus showing the vast technological advancements made over the

past millennia.

RHYTHMIC RELATIONSHIPS

Rhythm

(Ben Etkin)

Rhythm editing describes an assembling of

shots and/or sequences according to a rhythmic pattern of some kind,

usually dictated by music. It can be narrative, as in the clip from

Woody Allen’s

Bananas below, or, a music video type collage, as in the second clip from Sofia Coppola’s

Marie Antoinette. In either case, dialogue is suppressed and the musical relationship between shots takes center stage.

In Allen’s

Bananas, the use of a vaudeville-esque tune

recalls Charlie Chaplin and early cinematic comedy. Like Chaplin’s

characters, Fielding Melish’s actions and adventures continually result

in humorous misadventure. In the sequence below, he heroically expels

two thugs from a subway car. The length of the shots is determined by

the quick tempo of the piano recording: as the villains’ abuse of

innocent passengers reaches a climax, the shots become shorter and

shorter. The quick editing builds suspense before the hero

unpredictably rises and throws them off the train.

In the next sequence, from Coppola’s

Marie Antoinette, the only

logic connecting the shots is that provided by Bow Wow Wow’s song, “I

want candy”, and a few graphic matches. The sequence is a hallmark of

Coppola’s style – interweaving period decadence and frivolity with a

contemporary youthful exuberance – which is also distinctively feminine.

SPATIAL RELATIONSHIPS

Establishing Shot

(Ben Etkin)

The

Establishing Shot

or sequence serves to situate the audience within a particular

environment or setting and/ or to introduce an important character or

characters. The establishing shot is usually the first or the first few

shots in a sequence, and as such, it must be very efficient in

portraying the context. Typically, establishing shots are Extreme Long

Shots or Long Shots, followed by progressively closer framing.

Quentin Tarantino introduces his film Inglorious Basterds,

with an extreme long shot of the countryside, suggestive of rural

France. It is followed by a medium shot of the dairy farmer, who will

dominate the first scene. One of the man’s daughters is also shown,

first in a medium shot and then in medium close-up, hanging clothes.

Moreover, the sequence establishes the central conflict, with the

arrival of the German motor cars, shown in POV shots from the

perspective of the farmer and his daughter.

Oliver Stone opens his film

W. in the opposite manner. From an

extreme close-up, a combined zoom out and pan reveals George standing

in the middle of an empty ballpark.

The final clip, from the conclusion of the Japanese psychological

thriller, 2LDK (“2-Bedroom Apartment”), is another example of the

establishing shot composed in reverse order. This sequence shows an

incremental expansion of the frame (in multiple shots) to include

elements beyond the dead bodies and eventually the entire city of Tokyo.

Shot/ Reverse Shot

Shot/Reverse Shot is an editing technique

that defined as multiple shots edited together in a way that alternates

characters, typically to show both sides of a conversation situation.

There are multiple ways this can be accomplished, with common examples

being over the shoulder shots, angled shots, left/right alternating

shots, and often a combination of the three.

In the first clip below, from Terry Zwigoff’s

Bad Santa, we

see a standard over the shoulder SRS. This, combined with eye-line

matches between the two main negotiators shows how focused each is on

the other. The over the shoulder technique allows the viewer to see the

facial expressions of each character while listening or speaking. More

importantly, the over the shoulder technique creates a sense of space

between the characters greater than the actual distance between them.

This keeps the frame from being uncomfortably cramped, and also shows

the distance between the characters’ different standpoints.

The second clip is from director John Dahl’s Rounders. There is a bit of

an experimental aspect to the SRSs in the clip. As opposed to the clip

above, the SRS technique is used to distort space in such a way that we

observe less than there actually is. In reality there is an 8 or so foot

table separating the characters: the SRS lessens this to a point where

the scene seems almost intimate. We see the characters alternating left

and right sides, which is a standard ploy of continuity editing. Again,

eye-line matches are used to show how intensely each character is

focusing on the other.

Spatial Continuity: 180 Degree System

Eye-line Match

In an eye-line match, a shot of a character looking at something cuts

to another shot showing exactly what the character sees. Essentially,

the camera temporarily becomes the character’s eyes with this editing

technique. In many cases, when the sequence cuts to the eye-line,

camera movement is used to imply movement of the character’s eyes. For

example, a pan from left to right would imply that the character is

moving his/her eyes or head from left to right. Because the audience

sees exactly what the character sees in an eye-line match, this

technique is used to connect the audience with that character, seeing as

we practically become that character for a moment. Each of the

following sequences is from No Country For Old Men, directed by the Coen

Brothers.

In the first clip, five eye-line matches are shown in a sequence

that’s only a minute long. The first of these contains movement from

left to right, mocking Llewelyn’s motion as he walks up to the dead

body. We then see relatively still eye-line matches as Llewelyn looks

at man’s face, and then at the gun as he picks it up. The next eye-line

match is shown as Llewelyn opens the briefcase of money, which contains

a slight zoom. This zoom is not necessarily used to mimic Llewelyn’s

eye movement, but rather his thought and emotion, as the sight of all

the money understandably “brings him in.” The Coen brothers decided to

use so many eye-line matches in this sequence and in the rest of

Llewelyn’s journey so that the audience would come closer to

experiencing what he was experiencing.

In the second clip, portraying Anton’s unfortunate car ride, we see

multiple eye-line matches once again. The first and last eye-line match

simply follow Anton’s eyes as he looks at the road while driving. We

also see another eye-line match of Anton checking his rear-view mirror;

in this match you can gain an appreciation for how perfect the angle is,

mimicking exactly what the character sees. With these eye-line

matches, we feel almost as if we are driving the car, which makes the

crash all the more disturbing. As illustrated in these two sequences,

and throughout the rest of the movie, the Coen brothers wanted us to

gain perspective on both Llewelyn and Anton. Through this, we gain a

better understanding of the relationship between the hunter and the

hunted, one of the film’s major themes.

Cut-in and Cut-away

This sequence, taken from Tarantino’s

Sukiyaki Western Django (2007) provide an examples of the

cut-in.

Cut-out or away is the reverse, bringing the viewer from a close view

to a more distant one. The sequence opens with an extreme long shot of

the area’s landscape, a high-angled tracking shot (probably via

helicopter) –giving us a wide panoramic view of the area. A cut

suddenly transports the viewer somewhere within the landscape to a

medium shot of character lying on the floor in his room.

TEMPORAL RELATIONSHIPS

Continuity editing: The Match on Action

Match on Action is an editing technique used in

continuity editing that cuts two alternate views of the same action

together at the same moment in the move in order to make it seem

uninterrupted. This allows the same action to be seen from multiple

angles without breaking its continuous nature. It fills out a scene

without jeopardizing the reality of the time frame of the action.

In the first scene above, Peter Jackson uses matches on action to

give the chase a sense of dynamism. The viewer can never assume what is

going to happen next, as the scene is constantly shifting. He uses a

very complex version of match on action, jumping from close ups to far

away helicopter shots and back without a pause. It is almost dizzying,

yet thrilling at the same time. Be sure to keep your eye on the white

horse; this is the character we are following and although hard to see

at times it is present in every part of the clip.

The second scene is from Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky IV. Here we see a

different, simpler style of matches on action. The camera stays at

relatively the same level, with few zooms in or out. The matches on

action are used to keep the fight realistic looking, as well as to keep a

certain character in focus/the center of the screen.

The final sequence gives us a Point-of-View shot from the angle of the

“Genji” warrior (shown in white) to the “Heike” gunman in red as he is

shot to the ground. In this sequence, we also have an example of

continuity as the Heike man first falls to the ground and we cut to him

closer up on the ground in the same position. This Heike warrior is

first shown standing up; though he is very small, you can see him in the

distance. After the Genji warrior takes aim and fires at him, you

notice him drop in the background towards where the Genji warrior has

his gun aimed; the match on action comes as the camera cuts to him

falling down.

Parallel Editing

Parallel editing is a technique used to portray multiple lines of

action, occurring in different places, simultaneously. In most but not

all cases of this technique, these lines of action are occurring at the

same time. These different sequences of events are shown simultaneously

because there is usually some type of connection between them. This

connection is either understood by the audience throughout the sequence,

or will be revealed later on in the movie. The first clip is from

No Country For Old Men directed by the Coen Brothers, and the second is from

Batman: The Dark Knight directed by Christopher Nolan.

In this first clip, we see parallel editing used primarily to add

suspense to the situation. At first, the intervals between showing

Lewelyn and Anton are relatively long, but as they shorten later on in

the sequence, additional suspense is added. Just as we see in the

previous clips from the film, there are many eye-line matches shown for

both of the characters. This combination of parallel editing and

eye-line matches for each line of action allows the viewer to

practically experience both sides of the event first-hand.

The second clip offers a different kind of parallel editing in the use

of sound. The basement of criminals contains only diagetic sound, but

as the sequence cuts to the police raid, the voice of the man on the TV

carries over, becoming non-diagetic sound. This created the effect of

the man practically narrating what we see occurring with the police. In

this way, parallel editing can be used not only to add suspense but

also to narrate a line of action with another line of action.

Alternative transitions

Superimposition

Th following sequence is an example of

superimposition.

Superimposition refers to the process by which frames are overlapped,

either mechanically or digitally, in order to achieve a layered

transition. Japanese cinema sometimes uses traditional “kanji”

calligraphy superimposed over standard film in several ways; the first

of these being to illustrate a famous quotation or religious koan (a

phrase chanted to bring about enlightenment), such as this example in

which Tarantino says the Japanese proverb, “life is all about goodbyes”

(サヨナラだけが人生だ) with the same words superimposed over the screen.

Fade -in

In this sequence from Sukiyaki Western Django, the calligraphic message provides an example of the

fade-in.

The style used in “Sukiyaki Western Django” is reminiscent of

filmmakers such as Kurosawa, who used this archaic writing technique to

embed a sort of traditionalism into his media. All in all, this effect

has the added value of reminding us that though we are watching a

Western, there is a Japanese component that underlies all the events of

the film, and we cannot forget this in sight of the lush mise en scène

that encompasses the entirety of the piece.

ALTERNATIVES TO THE CONTINUITY SYSTEM

Long Take

(Grant Reed)

Long takes are simply shots that extend for a long

period of time before cutting to the next shot. Generally, any take

greater than a minute in length is considered a long take. Usually done

with a moving camera, long takes are often used to build suspense or

capture the attention of audience of without breaking their

concentration by cutting the film.

The opening scene from Robert Zemeckis’ Forrest Gump follows a

feather blowing carefree in the wind, eventually landing on the foot of

the protagonist who proceeds to pick it up and place it in his suitcase.

This scene acts as a metaphor for the whole movie, as the feather

represents Forrest. Just as the feather blows around for what seems like

forever, just going where the wind takes it until it eventually lands

in a safe place, Forrest seems to just blow aimlessly through life,

going wherever life and fate may take him with out too much

consideration of his own, until he eventually lands in a happy place.

The next long take is from Frank Darabont’s

The Shawshank Redemption. A

white bus is seen driving up the street towards a long building. As the

bus turns to drive around the building the camera goes straight over

the top of the building to reveal the vast expanses of Shawshank Prison.

Hundreds of prisoners in the yard are all seen walking in the same

direction, seemingly toward the same place. As the camera makes it to

the end of the prison yard the bus returns to the frame, meeting a group

of guards at the same spot all of the prisoners had been heading

towards.

This long take sequence, from Scorsese’s

Mean Streets, shows

Charlie (Harvey Keitel) in a state of barely coherent drunkenness. The

sequence was accomplished by attaching a Steadicam to the actor’s body

in such a way as to continually frame his face in close-up in spite of

his uncertain movements. The position of the camera serves to capture

the disorientation and estrangement of the character as he stumbles

around the crowded bar. The red color of the image, together with the

absurd musical accompaniment, helps to render the atmosphere of a seedy

night club.

Jump-Cut

(Nelson)

A Jump-Cut is an example of the elliptical style of editing where one

shot seems to be abruptly interrupted. Typically the background will

change while the individuals stay the same, or vice versa. Jump-cuts

stray from the more contemporary style of continuity editing where the

plot flows seamlessly to a more ambiguous story line. An example of

this editing style can be found in the following clips from Capote

(2005).

Hollywood-style Montage

(Nelson)

Montage also describes the approach used in commercial cinema to piece

together fragments of different yet related images, sounds/music, often

in the style of a music video. The following sequence, from Pretty

Woman (1991), is an example of the

hollywood style montage.

The film, starring Richard Gere and Julia Roberts, shows the main

character Vivienne as she transitions from a scantily-clad, unrefined

hooker, into Edward’s elegant, poised and well-dressed companion. The

soundtrack plays over the background as snippets of various clothing and

body parts are shown. In the concluding frame of sequence, the final

product, the “new Vivienne”, approaches the camera in a white, tailored

outfit and a ladylike hat.